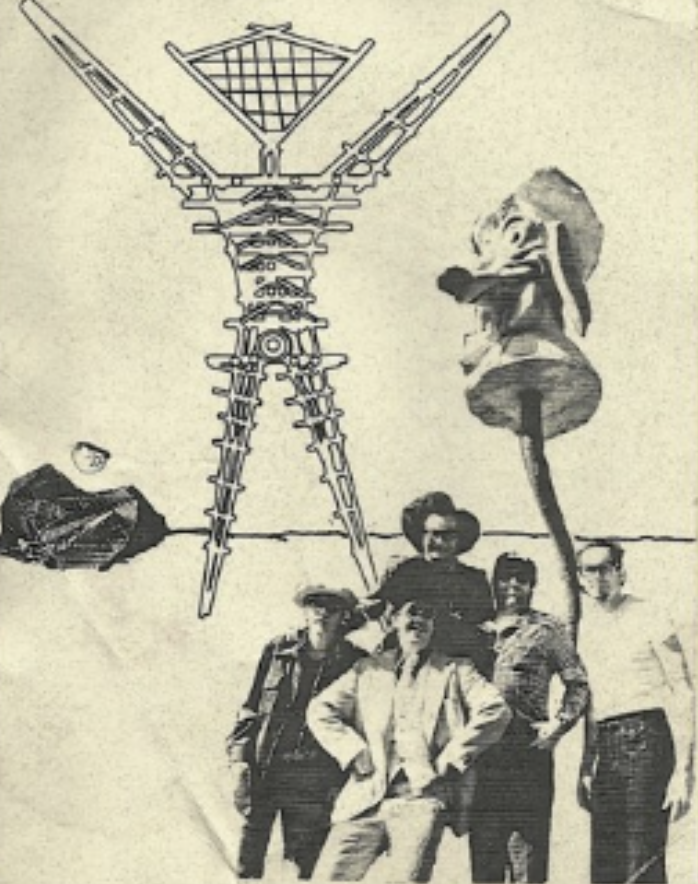

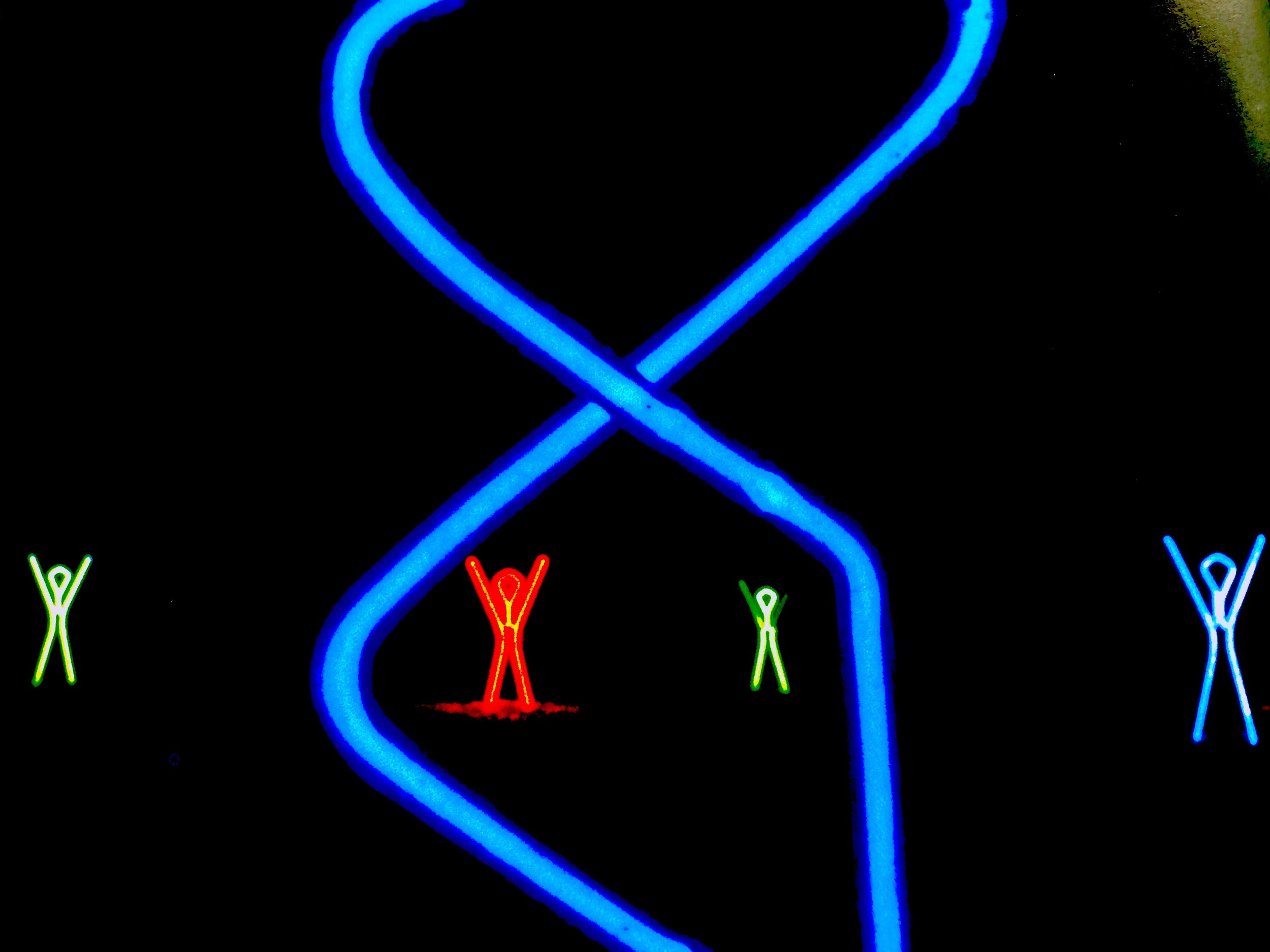

Pepe Ozan’s Lingram, his first work at Burning Man

Before 1993, Burning Man was little more than a Cacophony Society cocktail party in the desert, with guns and explosives. By 1993, a new vision began to emerge of an art and music “festival”, with the event formally being referred to as the Black Rock Arts Festival. During ‘93 to ‘95 there were still guns and explosives on the playa, art and music also began to take a more central roll. The population of the event doubled each year, with the Cacophony Society’s roll diminishing.

Art Arrives on the Playa: 1993 to 1995

1993: Black Rock Town is Born

In 1993, around 1,000 people attended the Friday to Sunday event. It was the year in which many significant developments occurred that started to move Burning Man closer to the event it was to become. Perhaps the most significant two devlopments were: Art arriving on the playa on a larger scale thanks to WIlliam Binzen and Desert Siteworks, and a town infrastructure being created.

Black Rock Town is Born

While calling it Black Rock City would be inaccurate, Black Rock Town is born by 1993, with all the infrastructure of a small community: A daily newspaper (the Black Rock Gazette), an off-season magazine (Building Burning Man), a radio station (Black Rock Radio: The Voice of the Playa), and a more formal city center.

Center Camp Stage

The camp was more structured as well, with it being arranged in a circle: Gateways formed by pairs of sculptures marking the four compass points marked out an inner camp. Each sculpture consisted of potato mashers and commercial egg beaters (an art piece called Desert Navigational Locators, created by William Binzen). This inner circle was surrounded by an outer circle of vehicles and Port-a-Potties. At one end of the circle was the yellow Ryder truck used to bring the Man to the desert.

The Ryder truck had a structure affixed to it, consisting of “two sides, one ‘sacred’ the other ‘profane’.” The side of the structure facing the Man “formed a theatrical facade designed as a feminine counterpart to the admittedly phallic figure of the Man.” The side of the central structure that faced away from the Man functioned as “a combination diner, cabaret and coffeehouse.”

Life on the Playa

Life on the playa was still loosely structured for much of the time. Driving on the playa, shooting guns and general tomfoolery was still the main attraction, but a more formal schedule of events was also forming:

Friday consisted of the initial raising of the Man (the Man would later be lowered and re-raised as had been done in prior years at BRC).

Next up was a communal potluck dinner.

After dinner a slide show and lecture on the geological and archeological history of the desert by Billy Clewlow (who had discovered the largest mammoth ever found in North America near Black Rock Desert) was scheduled and well advertised….but did not occur.

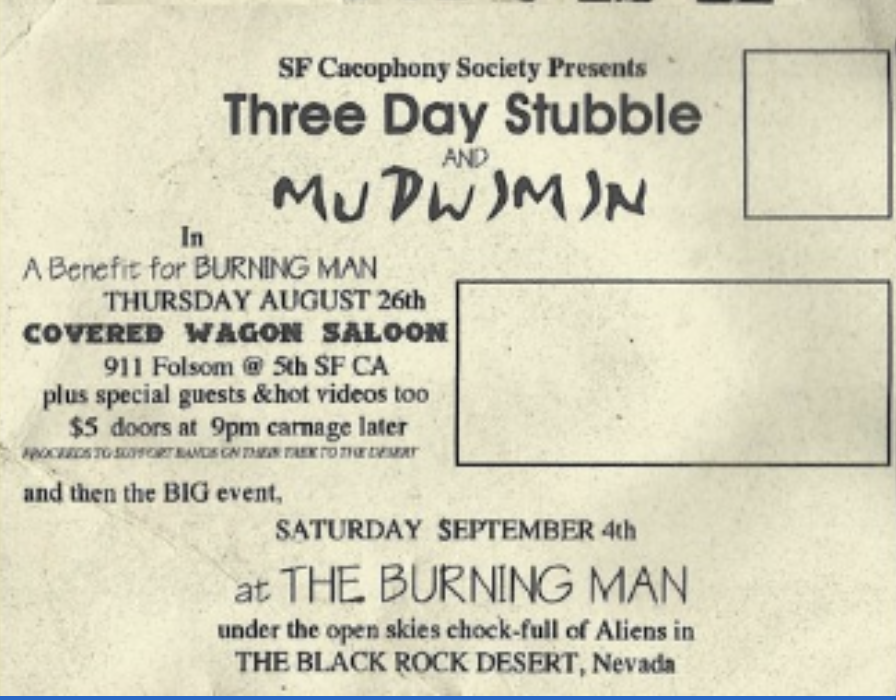

Saturday, just before sunset the Burning Man Fashion Show debuted, followed by a live concert by Three Day Stubble. The show was followed by Kimric Smythe and his wife strapping explosives to themselves and igniting them, forming the “Incredible Exploding Couple”, followed by more live music by Mudwimmin. Finally, people could enjoy a “rave” at the music camp, which was returning for a second year and again was stations almost a mile away from the main camping area.

Sunday started before dawn with the “Java Cow” ritual, in which Kimric would wear his Java Cow apparel, and hand out hot coffee at the base of the man. By the evening it was time to lower, and then ceremonially re-raise the Man, which was done by the community.

Crimson Rose and Will Rogers then did a fire show, which culminated with them lighting the Man. Another concert by Three Day Stubble and Mudwimin, followed by another trip to the “rave” camp for those that were inclined.

Art on the Playa

Doggie Diner head makes its debut

In 1993, art and music became more central to the playa experience.

A Burning Man icon arrived for the first time on the playa: the Doggie Head. In the first year the Doggie Head (falsely rumored to be stolen) was part of a stage, designed to host live music. The Doggie head became a fixture at Burning Man for many years, and now three doggie heads are beloved icons in San Francisco.

The bands Three Day Stubble and Mudwimin played live sets throught the week on the Doggie Diner Stage.

Other art projects included:

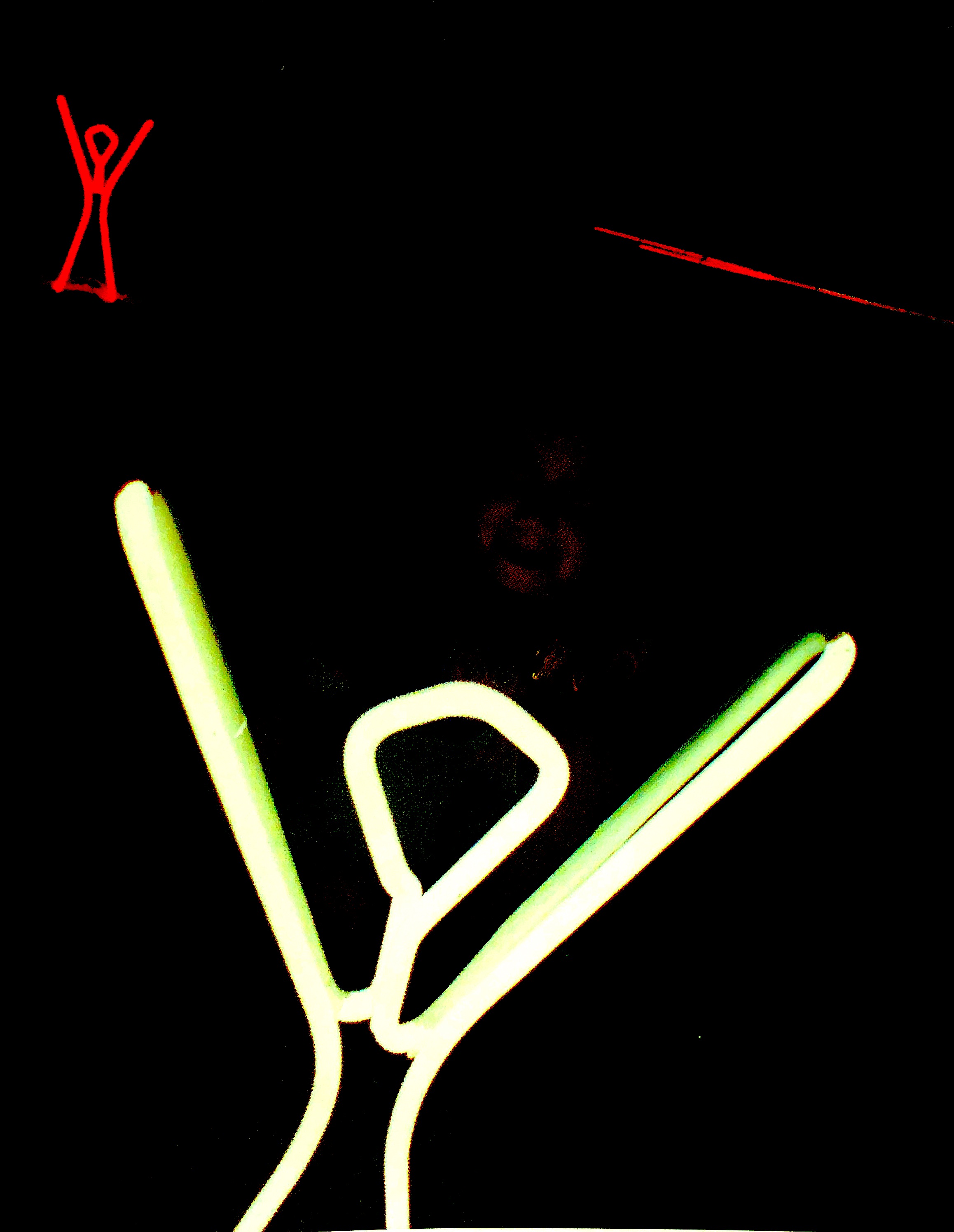

Authorities are Baffled, the desert’s first neon installation.

The Oasis was a tent with an indoor recirculating water fountain adorned with plastic snakes.

Lingam by Pete Ozan (who would become one of the playa’s most significant early artists) debuted. Ozan would bring Lingam back in different forms in multipe forms in future years.

The no-commerce rule was not yet in effect. One report noted:

‘I'm looking for some shrooms. Anybody want to sell some?’ Enterprising entrepreneurs hawk Burning Man T-shirts and mugs. A woman with cleavage bulging from a black spandex animal-print getup straight out of Married ... With Children sells tacos fried on a full-sized gas stove. Dozens of generators hum beneath the din of dozens of battery powered boom boxes.

Wacky fun still included a formal cocktail party before the burn. Food now included faux formal dinner, served on fine china for some…. continuing the theme of general zany entertainment.

1993 also featured the event participants never forget: “The Lightening Storm of 1993”. After the burn was over, people were leaping over the remaining embers. A man and a woman collided, resulting in the woman falling into the embers. The burned woman was pulled out of the fire and placed in a large horse shaped sail cart. Peter Dorty, as Santa, took the reins of the horse and three men pushed in against the shipping wind and dust.

The winds were high and the rain and dust combined for severe weather conditions. The HBO documentary team, on the playa for the first time, panicked and did the worst possible thing: They got in their RV and tried to drive to safety, inspiring others to panic and make the same mistake.

On Sunday mornings, as the sun rose on the last day of the Man’s corporeal life, a ritual developed. Kimric Smythe would appear at the feet of the Man wearing a cow’s-skull helmet, pushing himself on a little hand truck with a horse’s head on it. He was the Java Cow, and would distribute coffee to all those who approached with mugs. The Cow would ask if you wanted cream or sugar. The proper response was to shout back, en masse, “No! We like it black!'“ and down the brew. This ritual was memorialized in the 1995 Burning Man ticket, which shows Kimric in full cow.

Upon finishing their coffee, everyone would dash to his or her car, then a high-speed race, fifteen or twenty cars in a ragged row, would commence heading to the edge of the playa and the Black Rock Hot Springs, where they would watch the dawn.

In 1993, a banner demanding “No Specators” was hung on the side of a bus (which was quickly vandalized by the Billboard Liberation Front to read “NO S E TATORS”)

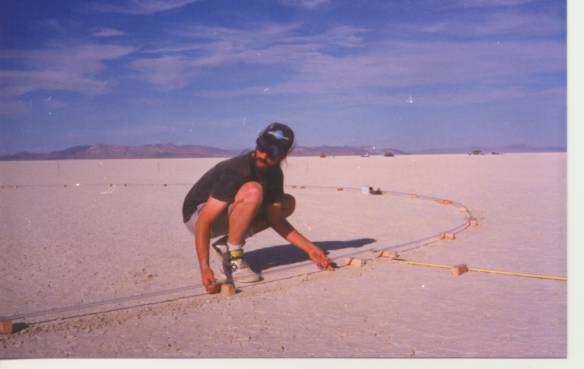

Desert Siteworks. From 1993 to 1995, William Binzen, a photographer, organized events that were more like what Burning Man later became. With the help of John Law and Michael Mikel, and other artists he set up multi week encampments at area hot spring (each year a different one: Black Rock Hot Springs, Trego and then Frog a/k/a Bordello).

A large area around Trego Hot Springs that had been a material storage for the railroad was repurposed (with the intent of returning the area to its original condition) into a colossal art canvas containing over twenty earthworks and surface installations. Rituals, performances (for the participants only – there was no audience) and ongoing fabrication and modification of large-scale installations went on for ten days. These sessions in 1992 at Black Rock Springs, 1993 at Trego and 1994 at Frog Pond Springs at Garett Ranch pioneered the “Intentional Community” philosophy that informs and inspires the best components and participants of the Burning Man Festival to this day.

Peter Doty

Peter Doty

Creator of the Theme Camp

Peter Doty noted about early burns “It always surprised me that people were doing art out there. I didn’t think of it as something people would necessarily do. I thought of it as more of a camping trip/party type of thing. So anytime anybody did anything, it was like, ‘Oh, wow, someone did something!’. And back then, people actually slept at night. There weren’t a lot of generators. In 1991, I’m not sure there were any generators.”

Doty is generally recognized as creating Burning Man’s first theme camp, although some argue other groups such as the Bolt Action Rifle Club in 1990, pith-helmeted adventurers portraying the spirit of soldiers of the Raj with tea and authentic weaponry predated his efforts. Doty himself bows down before the efforts of Vivian Perry. She pulled of something he remembers as “Elegant Camp” Vivian “was going all out for elegance, and it blew everybody’s mind. She had a champagne bucket and fresh-cut flowers. She was eating oysters and caviar off china and silver, and it was all over-the-top extraneous and superfluous and completely inappropriate, and that was what was so wonderful about it.”

“Vivian was the talk of the playa. She managed to stay pristine the entire weekend…. Her white silk blouse was completely spotless, and her black velvet riding pants looked like they’d just come out of her drawer. Not even any dirt on her boots…. Turned out she was taking four showers a day and had multiple pieces of the same outfit; [she also] had a little damp rag she was carrying around, wiping of her boots constantly. We hadn’t seen anybody do anything so conceptually obsessive out there yet.”

Doty, with ideas supplied by Lisa Archer and Amanda Marshall, formed Christmas Camp in 1993 - He dressed as Santa, constantly blasted tapes of Christmas carols, festooned the camp with decorations, and supplied boozy eggnog.

1994: The Rise of Art

The First Lamplighter Poles

The expansion of art continued in 1994, with additional installation art appearing, more performance art occurring and art cars/mutant vehicles becoming more significant.

The month before the 1994 Burning Man, the Somar Gallery held a fundraiser benefiting Burning Man and Desert Siteworks. For the first time, DSW was scheduled to occur simultaneously with Burning Man, kicking off on Monday, with Burning Man again occupying Labor Day weekend, while DSW continued. This would prove to be the last Desert Siteworks event, but many of the participants in DSW would morph into Burning Man, further pushing the Burn in a more artistic direction.

In 1994, around 2000 people would attend Burning Man, double the year before and the fifth year in a row of doubled population.

“Burning Man is an intensely participatory experience. We encourage spontaneous performance, costumes, and original campsite architecture. Bring musical instruments. Invent games. Respond to the desert. Make a statement. This year we invite participants to build shrines, altars, votive temples, etc. which express their conception of the desert environment. Here is a partial list of planned attractions.” ~ from the flier handed out at entrance gate in 1994.

Somar Gallery Show

The Man, August 4, 1994 at Somar Gallery, San Francisco.

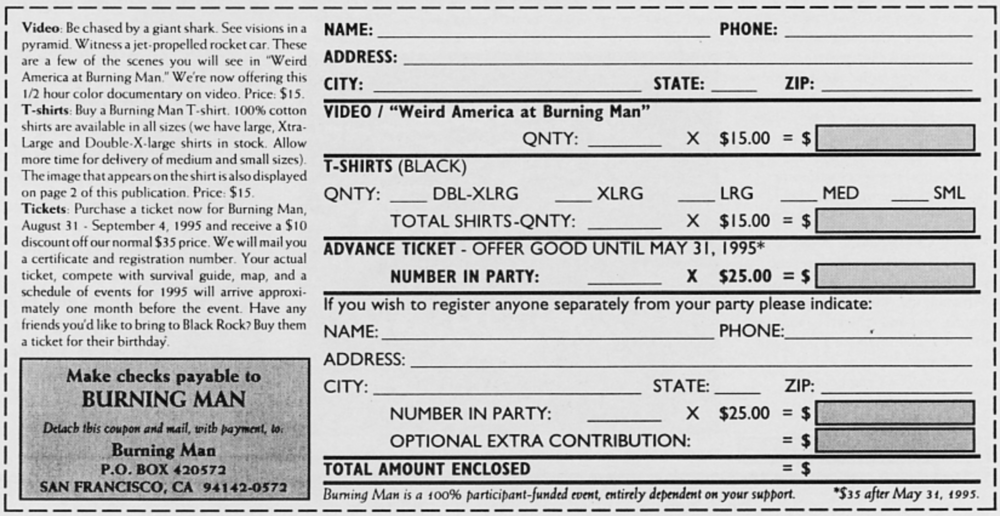

By 1994, the cost associated with hosting the event was increasing. Paid attendance was also increasing, and tickets was becoming slightly more formal. However, cash flow was still an issue, with various founder’s credit cards being used to bridge the funding gap.

To help have some source of funds prior to the events opening (gate collections were still the primary source of revenue in 1994), and to help offset some of the cost of the Desert Siteworks gathering, DSW and and Burning Man co-hosted a fundraising event at the Somar Gallery on August 4th and 5th, 1994.

For the show the man (designed and built under the lead of Larry Harvey’s roommate, Dan Miller and with neon by John Law. Not only did this expose the Burning Man event to more of the general public, but critically, it introduced it to a wide cross section of the Bay Area artist community, as well as the Bay Area media.

While the $3 admission did help the organizations, the event was covered in the Bay Area alternative papers, as well as in several art focused newsletters.

Media and the Man

Despite being a relatively small scale event, 1994 was the year in which Burning Man began to gain national and international media attention. The New York Times Sunday Magazine carried a two-page spread of the event. Various news agencies brought camera crews, including ABC Australia. Chuck Cirino brought a camera and made segments for his show Weird TV, and later used this footage to create the first feature length film on the event.

Internet Broadcast

Alfredo Lusa put up a tower with a yagi directional antenna and beamed a signal from the playa to a dish attached to a small tower next to a room at Bruno’s Motel in Gerlach. Burning Man rented room 30 and hooked a 56kbs dial-up modem to the phone line. The broadcast used an early form of the CU-SeeMe, which had been released the year before. The pictures were low resolution, and it took about a half-hour per photo.

Art Projects

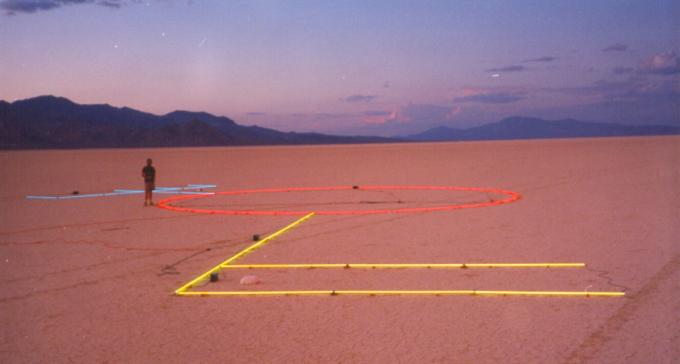

Participants in 1994 were promised an “avenue of art”: “This year the processional roadway leading outward form our camp will extend beyond Burning Man into the deep space of the desert. Along it we will locate works of Art.”

Church of the Pyramid Camera Obscura

by Chris de Monterey

This temple takes the form of that mysteriously powerful pyramid which stares back at us from dollar bills. Within its darkened sanctum is a camera obscura. A rotating lens mounted on the pyramid focuses a revolving panorama of the world outside upon a concave screen. Rituals include a ceremonial Camera Burning.

Fire Lingam

by Pepe Ozan

Lingram by Pepe Ozan, 1994

Pepe returned to Burning Man again in 1994 with another iteration of his Lingram. The 30′ chimney is made of playa mud over a rebar and metal mesh structure.

The final day, a fire was ignited in the Lingram, slowly reducing the work to the dust from which it originated. As it burned, the haunting cracks reminded some of the desert floor and others of their own mortality. Man recall the burning of this Lingram as an important point of inflection in the early Burning Man years.

Four Directions

by Ric Louchard; altars by Lynn Marsh

Four speakers were positioned at each compass point circling the Man and facing inward, creating four different sound environments. The 19-minute quadraphonic composition was timed to end at sunrise each day. Participants could walk through the sound field, blending or isolating any of the tracks playing in the immersive experiment.

Precious

Precious, Burning Man 1994

by David Lundquist and Frisco Rose.

A 16-foot long bronze dragon that breathes fire. The first fire projecting art piece that we can remember!

The Daygloasis

Daygloasis, by Graham Cruickshank, David Davenport and Gabriel Plumlee

For some reason, Daygloasis is absent from virtually all accounts of Burning Man history. But it was there! Described as “painted blacklit mosaic glowing on the desert floor.” Artists: Graham Cruickshank, David Davenport and Gabriel Plumlee.

It was located near the rave camp, which was nearly a mile away from the center camp. The photo to the right not only shows the art, but shows that

The Annual Performance Art Show

In 1994, Larry Harvey and Pepe Ozan hosted a “Annual Performance Art Show” featuring the following performances:

Spontaneous Combustion Theater

by the LA Cacophony Society

The LA Cacophony brought several dummies, loaded them up with fireworks and blew them up. Performance art may be a stretch, but it blew up real good. From the 1994 gate flyer: “Fire breathing poets and incendiary clowns trace the origin of spontaneous human combustion through this anarcho-burlesque, audience participatory theater intoxication ritual. It’s aesthetic anarchy with a smile!”

The Incredible Exploding Couple (now enlarged to ménage a tois):

As in past years Kimric Smythe strapped explosives to himself and his wife Heidi. The 1994 greeters book also noted that Robert McMullen would join the show, although we don’t remember him participating:

“Heidi and Kimric Smythe, joined this year by Robert McMullen, will again perform – their bodies festooned with fireworks and kinetic devices. (Complaints were voiced in 1993 that this daring duo did not actually explode, but merely showered sparks and rockets. This year, Kimric, eager to satisfy his public, promises to blow himself up).”

Crimson Rose and Will Roger Fire Show

A fire show by Will Roger and Crimson Rose wearing body paint by Jason Norelli. Together they ignited the Man, to end the year’s gathering.

Music on the Playa

“SHARKBAIT”: Described as a “retro-proto-apocoloytic band will bring their distinctive brand of cacophonous percussion to the Burn on Sunday night. Bring something to beat on.” Sharkbait was a San Francisco-based industrial noise band that was playing festivals in the early 90s. John Law noted “Sharkbait was one of the truly astonishing San Francisco ensembles. Kimba [Anderson] and bandmates Chris Taylor, Mr. Clean, Greg Slugocki and others created a unique, audience participation element for their one of a kind performances. Kind of a metal/noise/glam/industrial hybrid, Sharkbait would drag audience members up onto their stage set and, after outfitting them in welding chaps, gauntlets and full helmets, would hand them a sledge hammer and put them into chain link cages where the virtually frothing at the mouth fans turned performers would frantically smash the crap out of a seemingly endless pile of televisions…Priceless.”

RAVEI: SPaZ played the “rave camp”. It was reported that they “will be joined this year by the ‘ZIPPY Pronoia Tour to US ‘94’ direct from the Grand Canyon. (Pronoia is the sneaking feeling that someone is conspiring behind your back to help you.) Look for it late night approx. 1 mile East of camp.” SPaZ…Semi Permanent Autonomous Zone, included Terbo Ted, the first person to DJ at Burning Man.

1995: The Rise of the Theme Camp

Theme camps had been a part of Burning Man since at least Peter Doty’s Christmas Camp. But in 1995, the Burning Man organization began to significantly promote the growth of theme camps, including giving placement locations (the first placement), and even suggesting ideas for theme camps (several of which appeared on the playa).

1995 was also the year when many of the “old school” participants seemed to consistently complain that the event had grown too large. The unofficial slogan of the old guard was “Keeping the Playa Safe for Anarchy”, which was in contrast to where the event was heading. Formal placement for theme camps, a printed ticket, a daily paper, an alternative paper (“Piss Clear”), and international media attention was setting the event on a course that was in conflict with its roots.

Somar Arts Gathering

Burning Man returned once again in August to Somar art space in San Francisco to promote the event and to raise funds. The event took place over two weekends (August 4-5 & 11-12), and the Man was once again assembled and illuminated.

Advertised as “Out There (in Here)”, but referred to by Larry Harvey from time to time as “The Odd, the Strange, the Weird, and the Wholly Other” show, a reflecting pool was added for a dramatic effect. The event featured art, music and other performances. The Dance troupe Collapsing Silence\ performed with Sirens of Saturnalia and the musical group Hollow Earth. Magenta Crowe danced, and Timothy North played a 3-story drumming platform. Pepe Ozan and Wayne Scott created installment pieces. Ape Theater did performance art. John Law and Vince Koloski installed neon. Synapse created “a ritual environment of media immersion entitled ‘Ancestor Stones’".

Larry Harvey described the Man installation:

We installed the Burning Man in an upright position beneath the soaring vault of the former foundry’s 4-story high space. We equipped the inside of the figure’s head with a microphone, a speaker and a video camera. These were connected to a microphone, a monitor and headphones discreetly located in a curtained booth near the base of the statue. A rope and pulley fastened to a ceiling beam allowed participants to clamber into a boson’s chair and be raised high overhead by their friends. This, of course, required that they trust these friends. Suspended immediately adjacent to Burning Man’s large triangular face, participants were urged to talk to this authoritative presence and put questions to it. Those who lurked inside the curtained booth below would then supply the answers. Our sound system automatically transformed their voices into a deep basso profundo.

Event Organization

In 1995, Burning Man introduced a new layout for the event, based on a designed suggested by William Binzen, creator of Desert Siteworks. Over one of many extended discussions Binzen had with Harvey, Binzen had jotted down on two napkins a proposed sitemap for Burning Man, featuring two concentric circles. The resulting map featured a community space in the center, including a cafe, stages, vending areas, and the bulletin board. The pirate radio station (built by Gordon Burke) and Black Rock Gazette would also be located in the central area. Immediately surrounding it would be the “placed” theme camps and a more formal road (Outer Ring Road). Beyond that would be open camping. Again the “rave camp” would one mile away. The first Burning Man website was launched, featuring photos of the 1994 event. It was designed by Mark "Spoonman" Petrakis.

Setting up the event was becoming a larger production. Thirty-five people were involved in building the Man, lead by Dan Miller, over six weekends. Setup, tear down and clean up was requiring a larger crew and more organization. Flynn Mauthe (aka Bobby Wayne) became the de facto head of the cleanup crew that would eventually be called the DPW, and would hold that position until 2003, and along with Will Rogers would formalize the organization of the crew. (In 1996, Flynn would also lead construction on the Helco Tower). 1995 included the first trash fence, created by a guy named Ember, or Larry Breed, a Cacophony Society member. John Law remembers “They were all going crazy over trash blowing downwind, and Ember suggested it to the ops department. They should make a bronze plaque for that guy for starting the trash fence," John Law says. "He did it for years after I left, too. It was all Ember’s idea, and I regard him as a hero."

The Annual Theme is Conceived

In 1994, Larry Harvey and Pepe Ozan began what would become an annual gathering at Somart gallery to promote Desert Siteworks and Burning Man. During this period, influenced by William Binzen, Larry Harvey started to think of art more seriously as a cohesive element of the Burning Man Project, both on and off the playa. In 1994, art was for the first time arrange with some order to create an “Avenue of the Arts”.

While 1995 did not feature a formally announced themes, as did all later years, the concept of a theme was being discussed. A semi-official burlesque performance featuring some of the events' organizers was produced, and it focused on the struggle between “Good and Evil”. Burning Man now considers “Good and Evil” to be the first theme, but Harvey and the others involved in shaping the theme viewed this year as “planting the seeds” for the themes that were born in 1996. Larry Harvey described the burlesque show as a “scripted wrestling match”":

We constructed a raised platform surrounded by ropes in the central camp circle, and here the assembled forces of all that was good and all that was bad contended. It was a tag team affair that matched such contestants as Bo Peep (clinging to her inflatable sheep) against Olga, the she-wolf of the SS Elite. Richard Nixon, skillfully impersonated by John Law, was also afforded a turn. At a critical moment, when trapped in what appeared to be a paralyzing hold, he suddenly produced the lost fifteen minutes of White House tape. Uncoiling this, he strangled his opponent. Participants surrounding the stage castigated the referee — played by Ed Holmes, a veteran performer from the San Francisco Mime Troupe — and rabidly urged on their chosen champions. I was selected by our group to play Albert Camus.

At the height of this conflict, I issued out onto the stage, stopped the action, dismissed the wrestlers, and proceeded to explain to the assembled fans that good and evil are illusions. Our planet is a pebble in a void. Continents exist upon its surface like islands of stagnant pond scum. Warming to this bleak description, I evoked an existential vision of an empty and uncaring universe before which any action shrivels to inconsequence. The gathering mob murmured, stirring uneasily; the outraged wrestlers howled. Bounding into the arena, they hoisted the French philosopher overhead and threw him out of the ring. The finale devolved into chaos. It wasn’t clear which side had won.

Theme Camps

Around 30 theme camps appeared in 1995. As an inducement to help the growth of camps, the organization gave theme camps formal placement for the first time in 1995. The organization also suggested themes in its summer magazine, Building Burning Man, several of which ultimately did appear on the playa.

Theme camps had been around since Christmas Camp (or arguably earlier), however, these theme camps were typically two or three people camping together with a unified motif. By 1995, camps were beginning to become larger, and draw people who weren’t necessarily close friends before the event. For example, Art Car Kamp, promoted by Harrod Blank, brought together nearly a dozen art cars from all over the country, and propelled the art car/mutant vehicle to be a significant attraction of the event.

The Cathedral of the Wholly Sacred Camp was arguably the precursor to the modern temple - a tent where one could leave items they considered sacred (or would be interesting to be considered sacred). While many of the items actually left were more ironic that sacred, some items and photos represented significant mementos. Flash Hopkins was back with his McSatan’s Beastro, where he sold, traded and gave away burgers and beer. Bigfoot Plaza, hosted by the Portland Cacophony Society handed out thrift store shoes in exchange for a participant putting on a little show of song and/or dance. The publishers of the Black Rock Gazette, Lloyd Void and his wife Paisley Hayes, brought Tiki Camp back for a second year, serving drinks, and hosting a large tiki party. Most camps were small, like Camp Hasselhof, with five to ten members.

The First Cafe

The precursor to the Center Camp Café, the Café Temps Perdu (the café of lost time) first opened in 1995. P. Segal, the long-time manager of the Center Camp Café remembers that it “got off to a limping start”. Despite being the only structure in the center circle of the camp, no one knew it was there. It was positioned “so that the counter of the café looked down the lantern-lit Avenue of Art, and at the Burning Man at the very end. I said it should be there because then the workers could watch the burn from behind the counter.” On the second day a storm leveled the structure, leaving only the espresso machine standing. P recalls that “The community rose to the challenge, having finally seen the espresso machine, and immediately seeing the value in getting the source of caffeine in functioning order. Volunteers stepped in and re-fashioned some kind of structure for us to operate in for the next 24 hours.”

No Commerce

The idea of banning commerce started in 1994, but by 1995 Burning Man was more formally promoting a “no commerce rule”. In 1994, Flash was selling tacos, hamburgers and beer. Sebastian Hyde and Joe Fenton sold t-shirts, and Fenton also sold Tarot Cards inspired by Burning Man. Chris DeMonterey sold official Burning Man Blast Shields, transparent Plexiglas sheets through which to view explosions and fires. By 1995, the org was still selling t-shirts and VHS tapes to help fund the event. Flash was still selling food and beer, although McSatans was becoming a beg or barter system by 1995, with Flash alternating between teasing people for trying to buy food and teasing them for trying to get him to give them food. (Flash would continue to sell things now and then for many years, perhaps more as a way of demonstrating his social status at the event than to raise funds).

Even in light of the trend toward no commerce, the idea of pure gifting had not been fully formed. It was common to expect something in trade when doing handouts. Cigarettes and alcohol were common currency in 1995.

Publications

In the months leading up to 1995’s event, Burning Man published two issues of Building Burning Man magazine, and released the Black Rock Gazette as a daily magazine. Adrian Roberts also published the first issue of “Piss Clear”, an alternative fanzine/newspaper

The Ticket

Burning Man started 1995 around $2,000 in debt, despite doubling attendance every year. Cash flow was always an issue, but with the event’s growth, getting cash prior to people showing up on the playa was becoming a critical pain point. Credit cards were being used to fund operations, and while Michael Mikel and others were still putting down the plastic, the organization began to make a more significant push to get cash pre-event via early ticket sales, and the sales of the annual t-shirt as well as VHS copies of Burning Man related videos. In 1995, Chuck Cirino’s segments of “Weird America”’s coverage of Burning Man was being sold on VHS for $15 (see below).

The Vibe of the Event

By 1995, the transition from a Cacophony event to an arts and music events was starting to clearly show. While in the first few years, the event was quiet, where the only amplified music was a battery powered radio, by 1995 the formal stage was featuring rock and industrial music each night.

Explosives had always been a part of the event, but by 1995 burning things was more central, with not only the Man being immolated, but Pepe Ozan’s Lingam also being a large scale burn. Fire dancers and other performers were also showing up to participate. Toy Land was a camp that featured stuff animals and childhood toys loaded with explosives. FIreball, a game of rugby played with a burning ball debuted (see below). Kimric Smythe strapped explosives to himself, his wife and his father and ignited them. And Scot Jenerik played industrial music on f lamming metal drums.

Nudity was becoming more central to the event. In the first few years, there was nudity but it was limited. P Segal theorized that because everyone pretty much knew everyone else, there was less comfort being naked than in later years where anonymity played a larger role.

In 1995 and before, most people dressed in street clothing. Bikes weren’t much of a thing, although they were starting to appear more. The bikes that were there were often ten speed street bikes. Decorating bikes wouldn’t become widespread for several years.

It was common for anyone without clothing to be surrounded by men in jeans with cameras, in what modern participants would find extraordinarily creepy. Locals had heard about the events, and were beginning to appear as tourists to the event. In 1995, guns were still permitted and the drive by shooting gallery still existed. But the locals seemed less interested in talking about guns (which had been true in the past few years) and more interested in gawking. Adrian Roberts, recalls locals driving around and yelling anti-gay epithets. Erik Davis also recalls locals at the event in 1995:

Northwestern Nevada is no more a vacuum than the New World was in 1492, and interacting with gawking locals was part of the fun: dudes in dune buggies with Confederate flags, grinning cops, rosey-faced oldsters with bemused grins and plastic cups of Bud. I asked one off-roading gentlemen outfitted in full camouflage what he thought of the scene. He crossed his arms, studiously avoided my gaze, and shrugged. "Different kind of weekend," he drawled. Erik Davis: Terminal Beach Party

1995 was also the first year with rain during the event. On Saturday it rained and hailed, producing a double rainbow and a slick muddy playa. The “Mud Orgy” became a symbol of Burning Man, with naked people rolling around in a large mud puddle with a drum circle playing nearby (see video).

Art on the Playa

Larry Harvey, influence by William Binzen and Pepe Ozan, began to envision Burning Man as an art event, renaming the event “The Black Rock Arts Festival”. He envisioned the art telling some type of cohesive story, both by having some common themes and being organized on an “avenue of the arts”.

Pepe Ozan’s Lingam

Pepe Ozan return with his annual Lingam project, a large sculpture built out of playa mud that was burned at the end of the event.

The Camera Obscura returned in 1995, and two neon projects also appeared: It Came From Within and Little Men, two pieces that look similar to modern playa art projects.

Water Woman

Water woman was a continuation of shower as art theme, featuring a statute that would also provide participants a shower.

The Art Car Kamp brought around a dozen cars to the playa, thanks largely to the efforts of film maker and art car enthusiast Harrod Blank.

Music also played a far more significant role than in past years, with performances by Sharkbait (industrial), Polkacide (punk rock polka), Three Day Stubble (self-proclaimed geek rock), the Mermen (surf rock), the Screaming Divas (acapella), Jim Cert, and many others. The “rave” camp was also back, and again stationed about a mile away from center camp.