The Curious Story Behind the New Cary Grant (Look magazine, 1959)

by Laura Bergquist

Photography by Bob Vose

Cary Grant, Hollywood’s most splendid and elusive wild goose, recently popped into a journalism class at West Coast university as a surprise lecturer. He peered at his audience. Then, having apparently decided “there were no assassins in the room” (to quote a fascinated student), he loosened his tie and proceeded to speak with prayer-meeting candor. He confided that, in the past, he not only had been emotionally immature, painfully shy, egocentric and at fault for the failure of his three marriages, but also had been a masochist, “who kept putting myself in a position to be hurt.”

Grant’s new, tell-it-all frankness amazes old friends. To quote another blithe charmer and AngloAmerican, actor David Niven: “I’ve known Cary for 25 years, and he’s the most truly mysterious fried I have. A spooky Celt for 25 years, and he’s the most truly mysterious friend I have. A spooky Celt really, not an Englishman at all. Must be some fey Welsh blood there someplace. Gets great crushes on people like the late Countess di Frasso, or ideas like hypnotism, the moves on. Has great depressions and then great heights when he seems about to take off for outer space.

“My wife and I used to week-end with him in Palm Springs. He’d vanish, and we’d find him hanging from parallel bars, or doing push-ups, or in a trance on the floor mesmerizing his big toe. He does nothing by halves. He was an excellent swimmer, for example, but then he took lessons to become a perfect swimmer. He keeps great chunks of himself in reserve.”

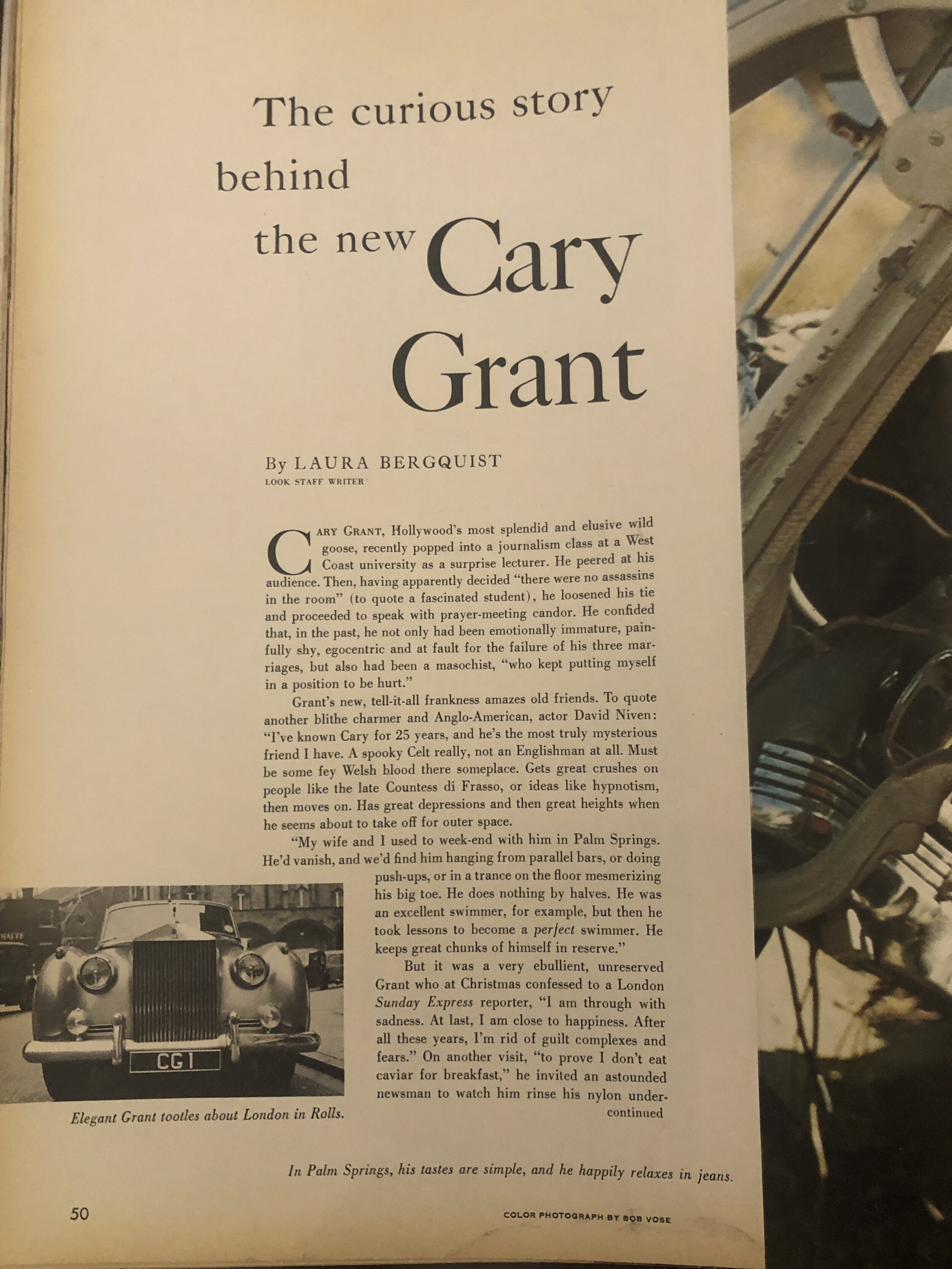

Elegant Grant tootles about London in Rolls.

But it was a very ebullient, unreserved Grant who at Christmas confessed to a London Sunday Express reporter, “I am through with sadness. At last, I am close to happiness. After all these years, I’m rid of guilt complexes and fears.” On another visit, “to prove I don’t eat caviar for breakfast,” he invited an astounded newsman to watch him rinse his nylon undershorts (a travel product of his own design) in a hotel washbasin. The homely gesture seemed curious for a man known the world over as a symbol of male elegance, but it did not tarnish Grants platinum image as the glossiest star left in Hollywood, where today’s lord of the celluloid jungle look like businessmen (William Holden) or talk like earnest beatniks (Marlon Brando). He still dashed about London in his $18,000 Rolls Royce, which differs from his $13,000 Rolls Royce, by the license plate CG 1 and the message “I LOVE Cary Grant,” scratched on a fender by a fan.

In Palm Springs, his tastes are simple, and he happily relaxes in jeans.

“All the loose ends of his life seem to be knitting together.”

“All the loose ends of his life seem to be knitting together,” reported Roderick Mann, an Express movie columnist, after lunching with Grant. “He seems much freer to talk about the past and even to explore his native England. Archie Leach [born Archibald Alexander Leach, a middle-class Bristol boy] has become Cary Grant.”

In Hollywood, Palm Springs, Bristol and London, I spend what now seem to have been several thousand hours trailing after, talking with and puzzling over the “new” Grant. I read his 20-odd scrapbooks I talked to his third wife, actress-writer Betsy Drake, whose nine-year marriage to Grant broke up last September; to his psychotherapist, Dr. Mortimer Hartman; and to leading ladies dating back to that salty charmer Mae West.

I discovered many baffling and contradictory Grants: the Lone Wolf who can’t bear to be alone; the Simple Grant, happily relaxing in Levis at “The Dump,” his Mexican adobe retreat in Palm Springs; the Perfectionist who drove one director to a hospital with nervos exhaustion; the Evangelist for new enthusiasms.

He is a tycoon and a tastemaker

There is also Grant the Tycoon, bargaining his six-figure earnings with a mind like an IBM machine. (Instead of taking a start’s usual fat cut for his new comedy, Operation Petticoat, Grant talked Universal-International into taking 10 percent of the gross-from his producing company.)

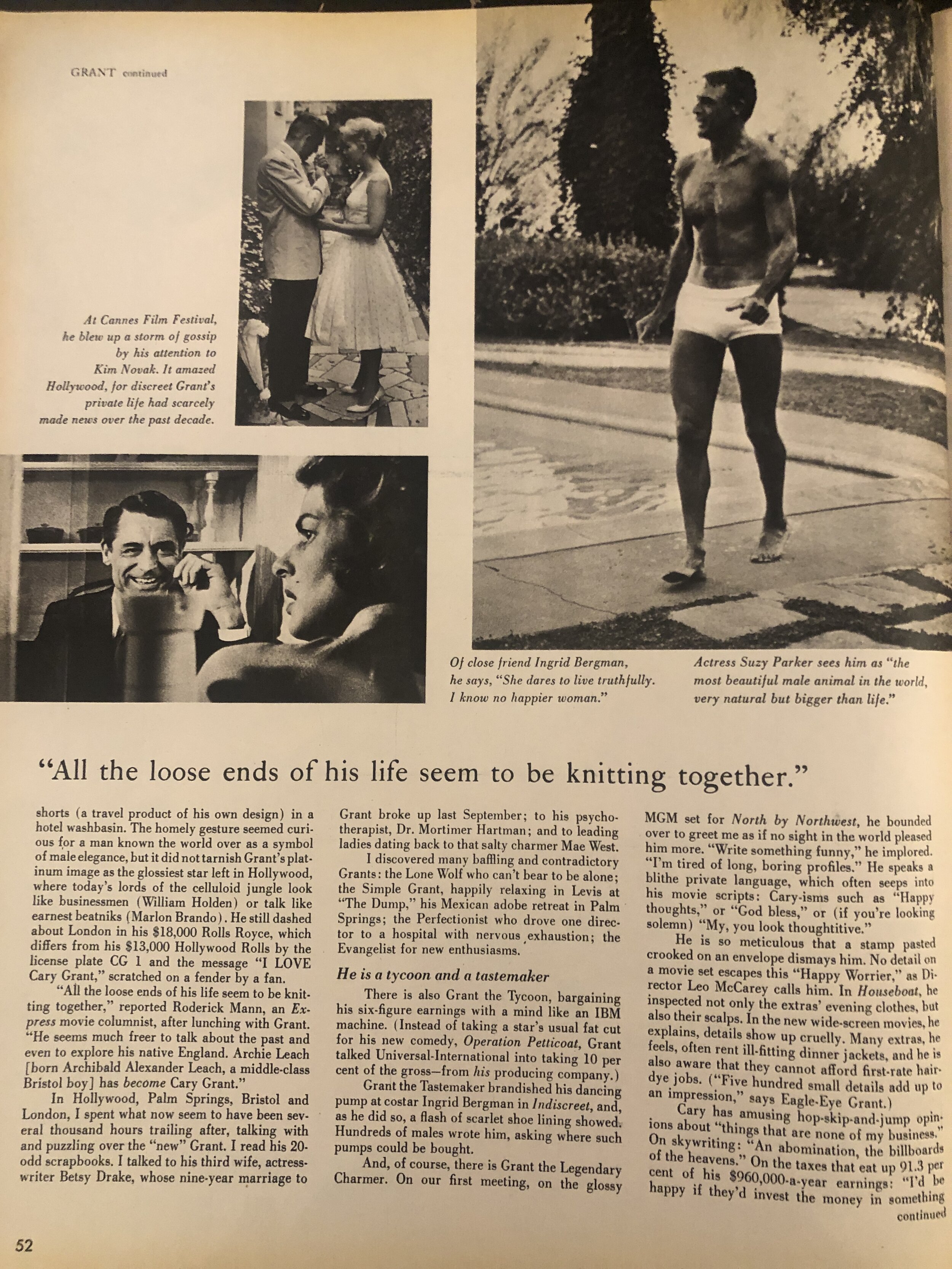

Grant the Tastemaker brandished his dancing pump at costar Ingrid Bergman in Indiscreet, and, as he did so, a flash of scarlet shoe lining sowed. Hundreds of males wrote him asking were such pumps could be bought.

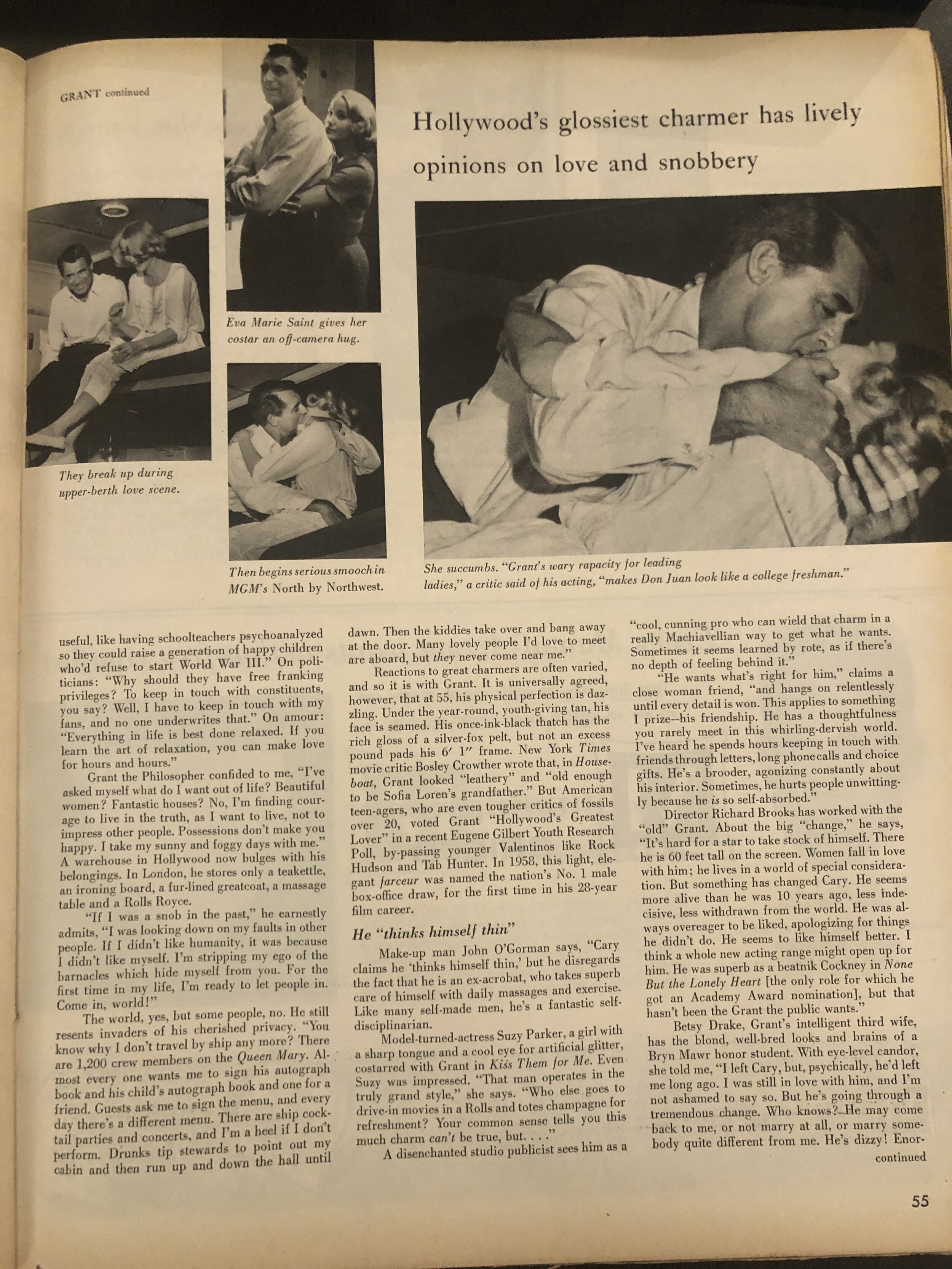

And, of course, there is Grant the Legendary Charmer. On our first meeting, on the glossy MGM set for North by Northwest, he bounded over to greet me if no sight in the world pleased him more. “Write something funny,” he implored. “I’m tired of long boring profiles.” He speaks a blithe private language, which often seeps into his movie scripts: Cary-isms such as “Happy thoughts,” or “God bless,” or (if you’re looking solemn) “My, you look thoughtitive.”

He is so meticulous that a stamp pasted crooked on an envelop dismays him. No detail on a movie set escapes this “Happy Worrier,” as Director Leo McCarey calls him. In Houseboat, he inspected not only the extras’ evening clothes, bur also their scalps. In the new wide-screen movies, he explains, details show up cruelly. Many extras, he feels, often rent ill-fitting dinner jackets, and he is also aware that they cannot afford first-rate hair-dye jobs. (“Five hundred small details add up to an impression,” says Eagle-Eye Grant.")

Cary has amusing hop-skip-and-jump opinions about “things that are none of my business.” On skywriting: “An abomination, the billboards of the heavens.” On the taxes that eat up 91.3 per cent of his $960,000-a-year earnings: “I’d be happy if they’d invest the money in something useful, like having schoolteachers psychoanalyzed so they could raise a generation of happy children who’d refuse to start World War III.” On politicians: “Why should they have free franking privileges? To keep in touch with constituents, you say? Well, I have to keep in touch with my fans, and no one underwrites that.” on amour: “Everything in life is best done relaxed. If you learn the art of relaxation, you can make love four hours and hours.”

Grant the Philosopher confided to me, “I’ve asked myself what do I want out of life? Beautiful women? Fantastic houses? No, I’m finding courage to live in the truth, as I want to live, not to impress other people. Possessions don’t make you happy. I take my sunny and foggy days with me.” A warehouse in Hollywood now bulges with his belongings. in London, he stores only a teakettle, an ironing board, a fur-lined greatcoat, a massage table and a Rolls Royce.

“If I was a snob in the past,” he earnestly admits, “I was looking down on my faults in other people. If I didn’t like humanity, it was because I didn’t like myself. I’m stripping my ego of the barnacles which hide myself from you. For the first time in my life, I’m ready to let people in. Come in, world!”

The world, yes, but some people, no. He still resents invaders of his cherished privacy. “You know why I don’t travel by ship any more? There are 1,200 crew members on the Queen Mary. Almost every one wants me to sign his autograph book and his child’s autograph book and one for a friend. Guests ask me to sign the menu, and every day there’s a different menu. There are ship cocktail parties and concerts, and I’m a heel if I don’t perform. Drunks tip stewards to point out my cabin and then run up and down the hall until dawn. Then kiddies take over and bang away at the door. Many lovely people I’d love to meet are aboard, but they never come near me.

Reactions to great charmers are often varied, and so it is with Grant. it is universally agreed, however, that at 55, his physical perfection is dazzling. Under the year-round, youth-giving tan, his face is seamed. His once-ink-black thatch has the rich gloss of a silver-fox pelt, but not an excess pound pads his 6’ 1” frame. New York Times movie critic Bosley Crowther wrote that , in Houseboat, Grant looked “leathery” and “old enough to be Sofia Loren’s grandfather.” But American teen-agers, who are even tougher critics of fossils over 20, voted Grant “Hollywood’s Greatest Lover” in a recent Eugene Gilbert Youth Research Poll, by-passing younger Valentinos like Rock Hudson and Tab Hunter. In 1958, this light, elegant farceur was named the nation’s No.1 Male box-office draw, for the first time in his 28-year film career.

He “thinks himself thin”

Make-up man John O’Gorman says, “Cary claims he ‘thinks himself thin,’ but he disregards the fact that he is an ex-acrobat, who takes superb care of himself with daily massages and exercise. Like many self-made men, he’s a fantastic self-disciplinarian.

Model turned-actress Suzy Parker, a girl with a sharp tongue and a cool eye for artificial glitter, costarred with Grant in Kiss Them for Me. Even Suzy was impressed. “That man operates in the truly grand style,” she says. “Who else goes to drive-in movies in a Rolls and totes champagne for refreshment? Your common sense tells you this much charm can’t be true, but. . . .”

His pursuit of Sofia Loren began in Spain. He found her a “child with the wisdom of the ages”.

A disenchanted studio publicist sees him as a “cool, cunning pro who can wield that charm in a really Machiavellian way to get what he wants. Sometimes it seems learned b rote, as if there’s no depth of feelings behind it.”

“He wants what’s right for him,” claims a close woman friend, “and hangs on relentlessly until every detail is won. This applies to something I prize-his friendship. He has a thoughtfulness you rarely meet in this whirling-dervish world. I’ve heard he spend hours keeping in touch with friends through letters, long phone calls and choice gifts. He’s a brooder, agonizing constantly about his interior. Sometimes, he hurts people unwittingly because he is so self-absorbed.”

Director Richard Brooks has worked with the “old” Grant. About the big “change,” he says “It’s hard for a star to take stock of himself. There he is 60 feet tall on the screen. Women fall in love with him; he lives in a world of special consideration. But something has changed Cary. He seems more alive than he was 10 years ago, less indecisive, less withdrawn from the world. He was always overeager to be liked, apologizing for thins he didn’t do. he seems to like himself better. I think a whole new acting range might open up for him. He was superb as a beatnik Cockney in None But the Lonely Heart [the only role for which he got an Academy Award nomination], but that hasn’t been the Grant the public wants.”

Betsy Drake, Grant’s intelligent third wife, has the blond, well-bred looks and brains of a Bryn Mawr honor student. With eye-level candor, she told me, “I left Cary, but, physically, he’d left me long ago. I was still in love with him, and Im not ashamed to say so. But he’s going through a tremendous change. Who knows? He may come back to me or not marry at all, or marry somebody quite different from me. He’s dizzy! Enormously stimulating! Younger than many young men I know.”

Among the earthy brunettes he has favored is Luba Otasevic, former basketball campion from Yugoslavia. Once Sofia Loren’s double, she has been signed to a Hollywood contract.

Over the past decade, Grant’s private life almost never made news. If you read of him at all, he was hobnobbing with tycoons rather than actors, cruising aboard Aristotle Onassis’s yacht or visiting Monaco’s pink palace. Sometimes, Betsy traveled with him; often, she stayed home and doggedly worked at her interests, among them photography, astronomy, and writing.

“Betsy was the kind of girl Cary had to force into going to Balenciaga’s,” says an artist-writer friend. “He gave her about $200,000 worth of jewels, which she lost during the Andrea Doria sinking. But ‘poshness’ never mattered to her. They were a perfectly delightful couple, who often seemed more like brother and sister than man and wife. Like two very bright, charming people playing a game of ‘Keep it gay, keep it light.’

Cary wrote the press release announcing their parting: “. . . Alas, our marriage has not brought us the happiness we fully expected and mutually desired. So since we have no children needful of our affection, it is . . . best that we separate for a while.”

Since they parted, Grant has blown up a storm of gossip. In May, he flew off to the Cannes Film Festival. There, he danced cozily with love goddess Kim Novak. (When told Grant was in his 50’s, she said artlessly, “Oh, I thought he was 40.”)

In England, a few months earlier, it was a sultry Yugoslav 23-year-old, Luba Otasevic, with whom he and his valet gypsied around the countryside. Luba is a girl “almost embarrassed by her physical opulence, to quote Producer Carl Foreman. A star lady basketball player in her country, Luba has been a penny-poor exile when Foreman hired her as a double for Sofia Loren in The Key.

Though separated from his third wife, Betsy Drake, he says, “I adore Betsy! And I owe her very much.”

When Grant met Luba, he was intrigued by her resemblance to Sofia. His pursuit of Miss Loren began in Spain in 1956 on the set of the costume epic The Pride and the Passion.

“It was Sofia’s first Hollywood picture,” a studio publicist recalls, “and, like a sponge, she soaked up all the lessons Grant offered her. Psychologically, she became very dependent on him. But personally, she played it cool.” Sofia cut the courtship off, during the filming of Houseboat, by her proxy marriage to her discoverer, Italian producer Carlo Ponti. When I asked Grant about Sofia, he sparred gracefully: “Who wouldn’t fall in love with her? She’s an adorable flirt, a child with the wisdom of the ages.”

Sine working in Spain, Grant has become a blue-jeans-and-brunettes man. “It’s murder to get him into black tie,” says a London hostess ruefully. “He now scorns fancy dress as he highest form of male peacocking. It may be a reaction against the era when he was being terribly grand.”

His new and startling penchant for exotic, earth brunettes, which began with his interest in Sofia, marks a sharp break with the past. Physically, the three women he married look amazingly alike and ran to the “cool, slim blonde” category, or, as he described them, “the smart type, with turned-up noses.” All had a society aura. Actress Virginia Cherrill, Charlie Chaplin’s former leading lady, married the Darl o Jersey after divorcing Grant; Barbara Hutton is one of the world’s richest women; Betsy grew up abroad with her carefree, colorful writer-father, but comes from Chicago’s staid hotel-building Drake family.

A baffling trio of wives

The difference in their temperaments, however, baffles Grant’s old friend David Niven: “Virginia was a frothy extrovert, Barbara was tucked away behind those battlements, and Betsy was one of the fey people, like him. But who knows, eh, what goes on in a marriage?”

Grant also has a penchant for “waifs,” in whom he may possibly see himself as a restless, unhappy 12-year-old who ran away from the Fairfield Academy near Bristol to join Pender’s acrobatic and comedy troupe. “Cary is never happier,” says a a woman friend, “than when he’s fussing over somebody, even when he’s in the most desperate trouble. But he can’t be forced. he must help in his own way, in his own good time.”

I heard Grant fuss about Luba: “Why, she’s just like Betsy used to be, the proud, young actress never taking proper care of herself, proudly rejecting help. I used to be that way.”

It was Bets who sparked his erstwhile interest in hypnosis, which he employed to cut out cigarette smoking and drinking (except for light wines) and to ease the clammy clutch of stage fright. Once, he wondered aloud to a luncheon companion whether he could hypnotize his silver thatch back to black. “Just thinking out loud, talking, influences your unconscious,” he says. “That’ why prayer is so helpful. During the filming of The Pride and the Prejudice, my back was carved up from sword fights. In four days, I healed the wounds by mentally directing the good oxygen toward the site of the cuts, and by mentally breathing out the impurities.”

Grant, a zealous missionary for L.S.D.

Today, Grant is a zealous missionary for an experimental form of psychotherapy. “All my life I’ve been searching for peace of mind,” he says. “I’d explored yoga and hypnotism and made attempts at mysticism. Nothing really seemed to give me what I wanted until this treatment.”

“The LSD sessions leave Grant either quite shaken or in a state of euphoria about his self-discoveries.”

The “treatment” involves taking lysergic acid (L.S.D.), a synthetic of the drug mescaline, used as a mind probe by such notables as Aldous Huxley. On Grant’s suggestion, I talked to his therapist, Dr. Mortimer Hartman, whom he calls his “wise Mahatma,” but whose taste in socks he “deplores”. Hartman is now preparing a paper, with two other West coast therapists, reporting on the treatment of 112 patients-among them Betsy and Cary Grant.

L.S.D., Hartman told me, “is a psychic energizer which empties the subconscious and intensifies emotion and memory a hundred times.” The patient has “waking dreams.” Since last November, Grant has taken to the couch on many a Saturday, swallowed L.S.D. pills and spent four to five harrowing hours probing his psyche, stimulated by mood music and Harman’s promptings. The sessions leave him either quite shaken or in a state of euphoria about his self-discoveries.

One Saturday, in a fantasy, he reported, his mind seemed to leave his skull and visit outer space. During another session, he thinks he relived his birth. Once, he says, he came away with a new insight into women. (“I love women-they’r the mothers of the earth, so often imposed on by men.”) “Luckily,” he added, with a Grant Twinkle, “I came out of the experience still speaking in a deep, masculine voice.”

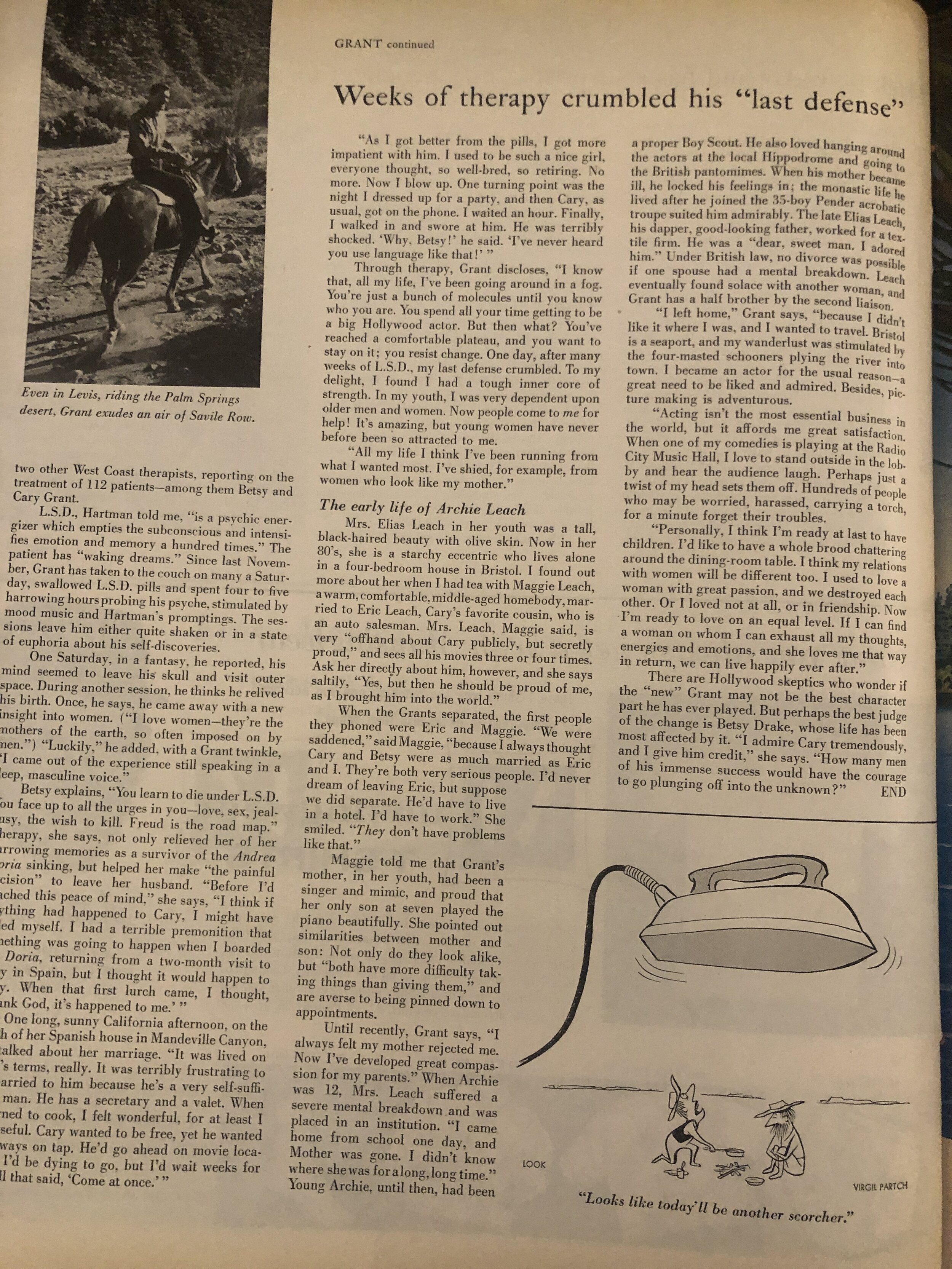

Even in Levis, riding the Palm Springs desert, Grant exudes an air of Savile Row.

Betsy explains, “You learn to die under L.S.D. You face up to all the urges in you-love, sex, jealousy, the wish to kill. Freud is the road map.” Therapy, she says, not only relieved her of her harrowing memories as a survivor of the Andrera Doria sinking, but helped her make “the painful decision” to leave her husband. “Before I’d reached this peace of mind,” she says, “I think if anything had happened to Cary, I might have killed myself. I had a terrible premonition that something was going to happen when I boarded the Dori, returning from a two-month visit to Cary in Span, but I thought it would happen to Cary. When the first lurch came, I thought, Thank God, it’s happening to me.’”

One long, sunny California afternoon, on the porch of her Spanish house in Mandeville Canyon, she talked about her marriage. “It was lived on Cary’s terms, really.. It was terribly frustrating to be married to him because he’s a very self-sufficient man. He has a secretary and a valet. When I learned to cook, I felt wonderful, for at least I was useful.. Cary wanted to be free, yet he wanted me always on tap. He’d go ahead on movie locations. I’d be dying to go, but I’d wait weeks for the call that said, ‘come at once.’”

“As I got better from the pills, I got more impatient with him. I used to be such a nice girl, everyone thought, so well-bred, so retiring. No more. Now I blow up. One turning point was the night I dressed up for a party, and then Cary, as usual, got on the phone. I waited an hour. Finally, I walked in and swore at him. he was terribly shocked. ‘Why, Betsy!’ he said. ‘I’ve never heard you use language like that!”

Through therapy, Grant discloses, “I know that, all my life, I’ve been going around in a fog. You’re just a bunch of molecules until you know who you are. You spend all our time getting to be a big Hollywood actor. But then what? You’ve reached a comfortable plateau, and you want to stay on it; you resist change. One day, after many weeks of L.S.D., my last defense crumbled. To my delight, I found I had a tough inner core of strength. In my youth, I was very dependent upon older men and women. Now people come to me for help! It’s amazing, but young women have never before been so attracted to me.

“All my life I think I’ve been running from what I wanted most. I’ve shied, for example, from women who look like my mother.”

The early life of Archie Leach

Mrs. Elias Leach in her youth was a tall, black-haired beauty with olive skin. Now in her 80’s, she is a starchy eccentric who lives alone in a four-bedroom house in Bristol. I found out more about her when I had tea with Maggie Leach, a warm, comfortable, middle-aged homebody, married to Eric Leach, Cary’s favorite cousin, who is an auto salesman. Mrs Leach, Maggie said, is very “offhand about Cary publicly, but secretly proud,” and sees all his movies three or four times. Ask her directly, however, and she says saltily, “Yes, but then he should be proud of me, as I brought him into the world.”

When the Grants separated, the first people they phoned were Eric and Maggie. “We were saddened,” said Maggie, “ Because I always thought Cary and Betsy were as much married and Eric and I. They’re both very serious people. I’d never dream of leaving Eric, but suppose we did separate. He’d have to live in a hotel. I’d have to work.” She smiled. “They don’t have problems like that.”

Maggie told me that Grant’s mother, in her youth, had been a singer and a mimic, and proud that her only son at seven played the piano beautifully. She pointed out similarities between mother and son: Not only do they look alike, but “both have more difficulty taking things than giving them,” and are averse to being pinned down to appointment.

Until recently, Grant says, “I always felt my mother rejected me. Now I’ve developed great compassion for my parents.” When Archie was 12, Mrs. Leach suffered a severe mental breakdown and was placed in an institution. “I came home from school one day and mother was gone. I didn’t know where she was for a long, long time. Young Archie, until then, had been a proper Boy Scout. He also loved hanging around the actors at the local Hippodrome and going to the British pantomimes. When his mother became ill, he locked his feelings in; the monastic life he lived after he joined the 35-boy Pender acrobatic troupe suited him admirably. The late Elias Leach, his dapper, good-looking father, worked for a textile firm. He was a “dear, sweet man. I adored him.” Under British law, no divorce was possible if one spouse had a mental breakdown. Leach eventually found solace with another woman, and Grant has a half brother by the second liaison.

“I left home,” Grant says, “because I didn’t like it where I was, and I wanted to travel. Bristol is a seaport, and my wanderlust was stimulated by the four-masted schooners plying the river into town. I became an actor for the usual reason-a great need to be liked and admired. Besides, picture making is adventurous.

“Acting isn’t the most essential business in the world, but it affords me great satisfaction. When one of my comedies is playing at the Radio City Music Hall, I love to stand outside the lobby and hear the audience laugh. Perhaps just a twist of my head sets them off. Hundreds of people who may be worried, harassed, carrying a torch, for a minute forget their troubles.

“Personally, I think I’m ready at last to have children. I’d like to have a whole brood chattering around the dining-room table. I think my relations with women will be different too. I used to love a woman with great passion, and we destroyed each other. Or I loved not at all, or in friendship. Now I’m ready to love on an equal level. If I can find a woman on whom I can exhaust all my thoughts, energies and emotions, and she loves me that way in return, we can live happily ever after.”

There are Hollywood skeptics who wonder if the “new” Grant may not be the best character part he has ever played. But perhaps the best judge of the change is Betsy Drake, whose life had been most affected by it. “I admire Cary tremendously, and I give him credit,” she says. “How many men of his immense success would have courage to go plunging off into the unknown?” END